Roots in the Soil, Eyes on the Horizon: Remembering Ahang Kowsar

Honoring a Lifelong Quest to Save Water, Soil, and Future Generations

Three weeks ago, my father passed away. During my 21 years in exile, I had only one chance to see him—for three precious days, 12 years ago, in France. Being so far from him, especially when I needed his guidance most, has been one of the cruelest punishments imposed by a ruthless regime. He was not only my father but my mentor, particularly in water and environmental stewardship.

Professor Sayyed Ahang Kowsar was a pioneering scientist who devoted his life to nature-based solutions for conserving water and soil. His concerns extended far beyond Iran, sharing his knowledge on international platforms and advocating for nature and humanity alike. He was a firm believer in environmental justice.

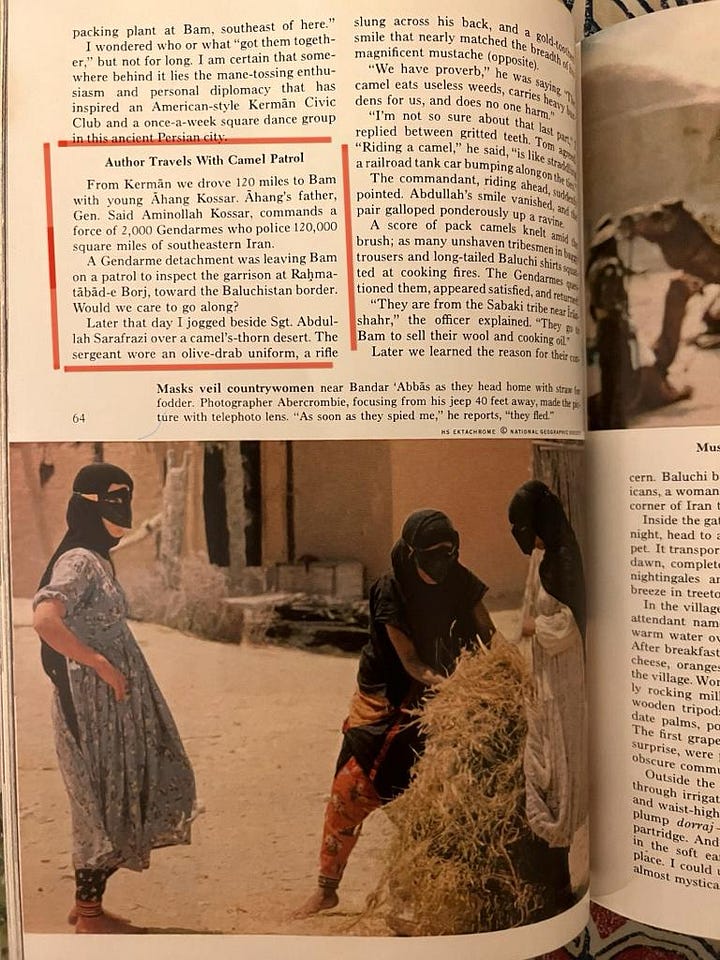

He came from a distinguished military family, where expectations leaned toward following in the footsteps of his father, General Sayyed Aminollah Kowsar—a decorated anti-corruption officer and a Sufi. But Ahang chose a different path. In his mid-twenties, his father, then the commander of the Gendarmerie in southeastern Iran, assigned him an unusual mission: to accompany a National Geographic team in a region threatened by gangs and smugglers. This experience, protecting foreign journalists in dangerous terrain, made a lasting impact on him. Shortly after, in 1961, his father, who had confiscated millions in illegal substances from the Shah’s twin sister, became the target of powerful adversaries and survived alleged assassination attempts. It was around this time that Ahang, at 25, left for Utah State University, and later, Oregon State, to study soil sciences.

At OSU, he was fortunate to find a like-minded mentor, Larry Boersma, who shared his passion for preserving soil and water resources. After completing his master’s degree, Ahang returned to Iran, married, became a father, and poured his energy into developing methods to combat soil degradation and using floodwaters to fight desertification. He later returned to OSU to complete his PhD. This time, I was there—a curious boy witnessing his dedication, his extra hours in the lab, all in service of a larger purpose: finding sustainable solutions.

When we returned to Iran in 1976, he fully committed himself to safeguarding Iran’s water and soil. We left the comforts of Tehran for impoverished rural areas, where we spent long stretches living in a caravan so he could pursue his mission.

Right after the 1979 revolution, he was invited by the newly appointed minister of agriculture to serve as deputy minister. However, as a committed researcher and scientist, he declined the prestigious role in the capital, choosing instead to dedicate himself to serving the people in the rural areas of Fars province. There, he pioneered strategies to combat desertification and harness flash floods to recharge depleted aquifers. His work not only preserved the land and gathered precious water but also reversed migration trends in these areas. People who had left due to severe water scarcity returned, finding renewed opportunities, and many achieved prosperity as groundwater flowed once more in their arid farmlands.

In 1988, foreseeing the long-term impact of climate change, he warned the country’s leaders about the critical need to adapt. He urged them to reconsider their water and food production strategies to prepare for a changing climate—a visionary call that underscored his deep commitment to Iran’s environmental future.

He had always hoped I would join him in the mission to save and preserve Iran’s precious natural resources, and as a journalist, I chose to raise awareness through media. This effort, however, had unintended consequences when one of my op-eds caught the attention of President Khatami, who summoned me to explain my statements.

In that piece, I warned the government that its water policies were leading the country toward worsening conditions. I detailed how the dam-building industry was pushing Iran down a perilous path. At the president’s office, with my father by my side, I laid out my concerns: I told President Khatami that his policies of diverting water from one basin to another, along with ambitious but unsustainable water management projects, would ultimately weaken the nation. I cautioned that these actions would steer Iran’s future away from prosperity and set it on a course toward disaster. The outcome was swift and severe: censorship, followed by intolerable pressure and escalating threats, leaving me with no choice but to flee.

His unyielding dedication to protecting Iran’s groundwater and soil resources eventually brought him into conflict with the Islamic Republic’s powerful water mafia. They harassed him persistently, subjecting him to repeated interrogations. In recent years, his outspoken opposition to a dam project near Shiraz led to years of court summons, questioning, and threats. Even while battling cancer, he courageously chose to forgo life-prolonging treatments, opting instead to endure pain to complete his work.

In his final years, despite the debilitating effects of cancer and the unrelenting pain of metastasis, he remained steadfast in his role as a guide and mentor.

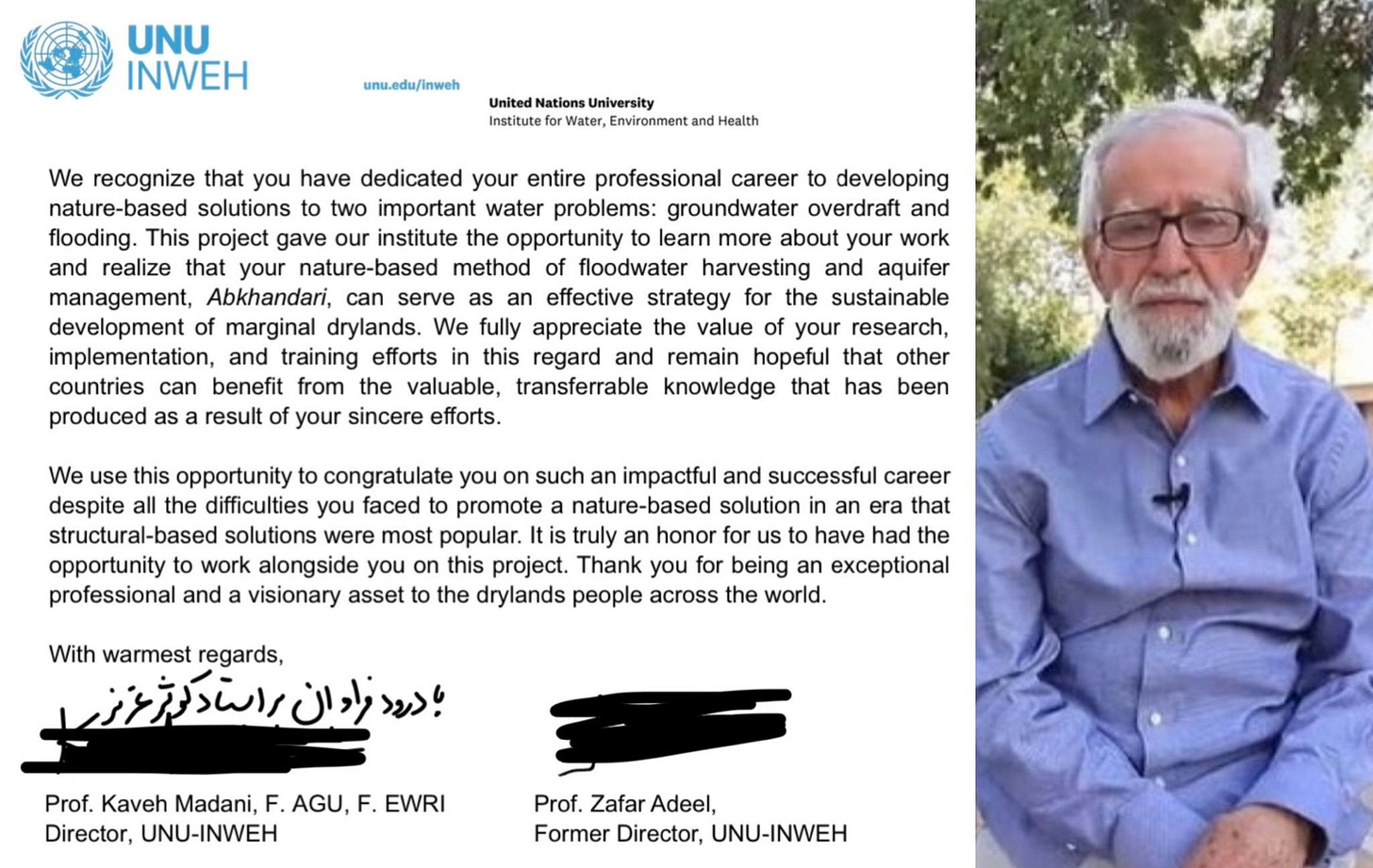

He was celebrated internationally, with leaders at the United Nations University recognizing his unwavering commitment to protecting arid and semi-arid regions from further degradation and worsening water scarcity.

In his last days, as he drifted in and out of consciousness, he continued to share his wisdom whenever possible, leaving behind a legacy defined by courage, dedication, and resilience.

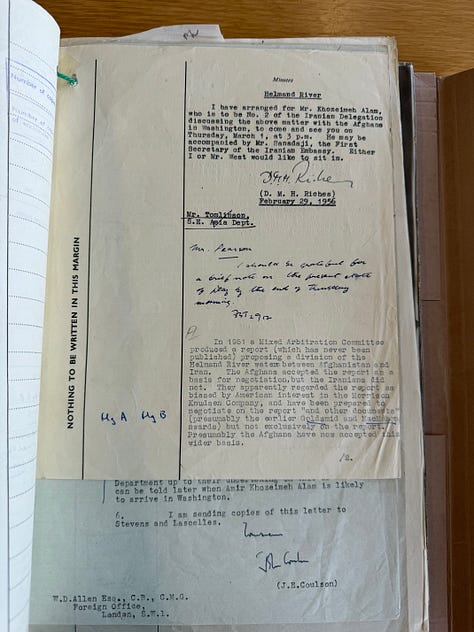

During our last conversation, just two days before he passed, I told him about documents I had uncovered in the UK National Archives detailing British-Iranian water management projects following WWII. Though intended to improve conditions, some of these initiatives had tragically harmed Iran’s water resources. Speaking each word caused him visible pain, yet he mustered the strength to offer invaluable insights into the historical missteps that had scarred Iran’s water, soil, and environment. His commitment to teaching and guiding me remained unwavering, an enduring testament of his spirit, until his very last breath.

So sorry to read this, Nik. My condolences to you and your family.